May the Force Be with You: A Practical Approach to Creating Meaningful Change in Times of Uncertainty

“Humans aren’t as good as we should be in our capacity to empathize with feelings and thoughts of others, be they humans or other animals. So maybe part of our formal education should be training in empathy. Imagine how different the world would be if, in fact, that were ‘reading, writing, arithmetic, empathy. ” – Neil deGrasse Tyson

After reading a few of my recent posts, a family member reached out to remark of her amazement of the depth to which I had given thought to the relationship between art and life. She never thought that music, for example, could represent much more than an opportunity to escape life’s daily rigors and reward oneself for a job well-done. I thanked her, but also clarified that the point of those posts was not just to create a link between music and life. Rather, it was intended to provide a roadmap through which readers could make sense of what is happening in today’s world. Her response was what I am sure most other writers want to hear after audiences engage with their work: “Why?”

Now, given enough time, I think I could have come up with a response that moved mountains, but rather than do that I considered what she was getting at, which was: what am I really trying to accomplish by sharing my insights and experiences on the impact that music has had on my life? And, in this case, it was this: I wanted to provide you all with perspective on how you could do better than I. It was with that in mind, however, that I quickly realized I had been remiss (or perhaps strategic) in explaining how exactly you could do better. So here goes…

Change & Failure

Usually when we speak about addressing difficulties or challenges in our lives we do so in the context of “we or I need to change.” Change, in this context, implies doing things differently, a response rooted initially in avoiding or reconciling the consequences of doing wrong. Over the past 5 months, we have heard plenty about the need to do things differently, but, each time, I feel like we are slightly missing the point. Certainly, failure can provide a useful lens through which we can gain insight into being better people as it provides clear and specific goalposts on how to act. But so, too, can operating from the premise that we all possess unique insights and experiences, which when used compassionately and strategically can add value for others in the right circumstances. Think of this in the context of the glass half-full or half-empty analogy: do I need change because it hasn’t worked previously or do I need to change because there is benefit to constantly challenging myself to do better?

The Mentor and Mentee

Consider the example of the relationship between mentor and mentee. Other than some pretext around appropriate interaction, there are very few rules governing how one individual shares their perspective with another around how they navigated life and career. The playing field is dictated by two things: 1) the degree to which the mentor can offer insights that are pertinent to the mentee and, most importantly; 2) the actual experiences and corresponding insights that the mentee seeks to leverage from the mentor for their benefit.

This transactional relationship, however, depends either in part upon the mentee’s ability to articulate the opportunities and challenges they face or, more often than not, the mentor’s ability to tease out and reconcile those needs in a manner that adds value. This same logic can apply to supervisor and employee; parent and child; and spouse and spouse. Now, ask yourself: how often does the mentee clearly articulate the problem so the mentor can address their need? How about the employee? Child? Fellow spouse?

The Role Of Empathy

One’s ability to identify, define, and evaluate human need is ultimately rooted in empathy. Change, when examined through this lens, is thus about doing things strategically or better—shorthand for innovation. And leadership is the outcome of leveraging empathy and the ability to relate and connect with people for the purpose of creating positive change/innovation. When Drew, for example, speaks about utilizing your values as a means to define why you matter, what I feel he’s really talking about is the importance of self-empathizing as a means to becoming more purposeful about how you’ll innovate for yourself and others. And, while he often shares stories of friends, colleagues and the like who have exemplified this so as to show that it is a behavior which we all can and should aspire towards, we can also find many examples of the musicians who we know and love who have attracted and sustained our interest and loyalty by employing empathy of the audience and conditions in which they live. There is a breadth of examples to choose from here, but I wanted to highlight one prominent example which most readers would know or be somewhat aware of.

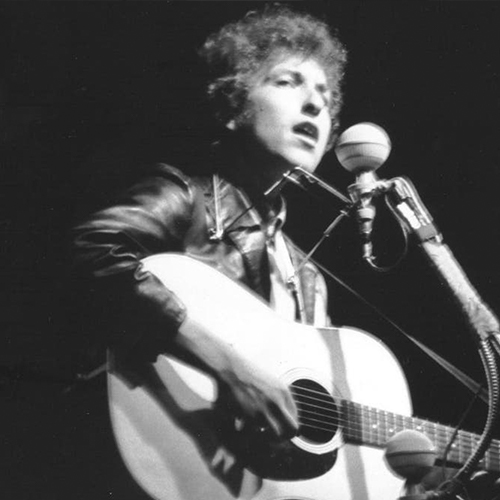

Bob Dylan

Bob Dylan’s influence on popular music is incalculable. As a songwriter, he pioneered several different schools from confessional singer/songwriter to winding, hallucinatory, stream-of-consciousness narratives. As a vocalist, he broke down the notion that a singer must have a conventionally good voice to perform, thereby redefining the vocalist’s role in popular music. And, as a musician, he sparked new several genres including electrified folk-rock and country-rock. For a brief period during the early 1960s, he was deemed by pundits and audiences to be” the voice of his generation”. For most, that would be a ticket to lifelong success. But that wasn’t Dylan. Ever the artist and poet, Dylan was heavily influenced by what was happening around him and gradually began to shift his music new-and-exciting heights. Heavily inspired by poets like Arthur Rimbaud and John Keats, for example, his writing gradually began to take on a more literate and evocative quality by the mid-sixties. Around the same time, he also began to expand his musical boundaries, adding more blues and R&B influences on his songs. In 1964, Dylan would record a set of original songs backed by a loud rock & roll band for his album, While Bringing It All Back Home. And then, months later, he played the Newport Folk Festival supported by the Paul Butterfield Blues Band.

For the folk purists, this was a breaking point and the audience greeted him with vicious derision. This derision continued in the ensuing months, which would eventually result in him becoming disenchanted and stepping back from the spotlight for a period of time during the 1960s. Dylan would famously remark during this period that he “didn’t belong to anybody then or now” in response to the folk community’s dismay and perceived betrayal for his new artistic direction during this period. Despite the purists’ horror at an electrified Dylan, the acoustic hero of the protest movement, they were also faced with a sudden dilemma (which Dylan surely must have known): either go along with it or stay put. And come along they would. “When Dylan shouted his electric refusal to work on Maggie’s farm,” says author Elijah Wald, “it was a declaration of independence for what was not yet known as the counterculture.” The furor over Dylan’s decision to go electric also mirrored the tensions and conflicts that were arising in America in 1965.

The issue of Vietnam was becoming ever more divisive, it was the year of the Free Speech Movement, the Merry Pranksters’ acid tests and the Watts Riots, which happened two weeks after Newport. In retrospect, Newport thus became the point where rock music replaced folk music as an outlet for creative-social-political expression with Dylan as its champion. “The [Newport] Folk Festival lasted four more years,” says the festival’s co-founder George Wein, “but after that we were no longer ‘It’, we were no longer hip, we were no longer what was happening. We were just old-time folk singers.” By plugging in, Dylan thus took the standards of folk, and a large proportion of its audience, with him into another realm. As the influential late DJ Charlie Gillett put it, “folk existed in a world of its own until Bob Dylan dragged it, screaming, into pop.” Wald also contends that the Newport performance marked “the iconic moment of intersection, when rock emerged, separate from rock-n-roll, and replaced folk as the serious, intelligent voice of a generation” and served as notice that Dylan would rather make deliberate artistic choices than merely grab at the brass ring.

Dylan’s path to “plugging in” and ultimately his achievement of creative freedom and public acceptance serves a wonderful example of a musician understanding their worth, while also strategically relating it to the conditions and times in which they exist. It would be incorrect to assume that Dylan wasn’t keenly aware of what was happening around him and able to pinpoint how exactly he needed to evolve so as to remain true to his passions while also creating the great impact on the audience. After all, it was well-documented by fellow band members and road staff that the always-spirited Dylan took the backlash as a challenge, a chance to prove the strength of his material by winning over the doubters. Nevertheless, his story serves as an important reminder that change to do better as opposed to do differently can have staying power and help each of us to navigate uncertain times.

If you would like to join me on a journey in discovering how other musicians have leveraged self-awareness and a keen sense of the conditions in which they operate to stimulate and promote their creative freedom so you, too, can be inspired about how to create positive impact/change for yourself and others, consider the following artists as a starting point:

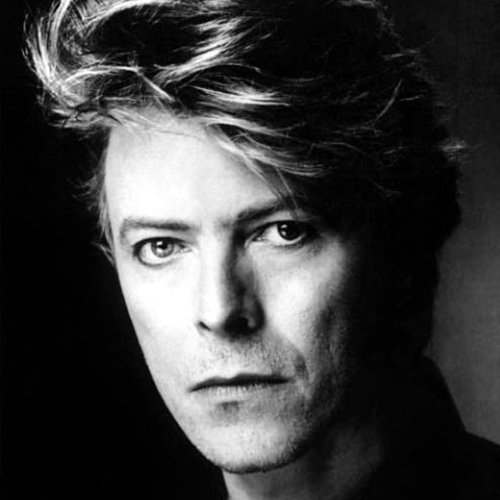

David Bowie:

The cliché about David Bowie is that he was a musical chameleon, adapting himself according to fashion and trends. While such a criticism is too glib, there’s no denying that Bowie demonstrated a remarkable skill for perceiving musical trends at his peak in the ’70s. After spending several years in the late ’60s as a mod and an all-around music-hall entertainer, Bowie reinvented himself as a hippie singer/songwriter. Prior to his breakthrough in 1972, he recorded a proto-metal record and a pop/rock album, eventually redefining glam rock with his ambiguously sexy Ziggy Stardust persona. Ziggy made Bowie an international star, but he was not content to continue to churn out glitter rock. By the mid-’70s, he’d developed an effete, sophisticated version of Philly soul that he dubbed “plastic soul,” which eventually morphed into the eerie avant-pop of 1976’s Station to Station. Shortly afterward, he relocated to Berlin, where he recorded three experimental electronic albums with Brian Eno. Even when he was out of fashion in the ’80s and ’90s, it was clear that Bowie was one of the most influential musicians in rock, for better and for worse. Each one of his phases in the ’70s sparked a number of subgenres, including punk, new wave, goth rock, the new romantics, and electronica. Few rockers have ever had such lasting impact.

Miles Davis:

A monumental innovator, icon, and maverick, trumpeter Miles Davis helped define the course of jazz as well as popular culture in the 20th century, bridging the gap between bebop, modal music, funk, and fusion. Throughout most of his 50-year career, Davis played the trumpet in a lyrical, introspective style, often employing a stemless Harmon mute to make his sound more personal and intimate. It was a style that, along with his brooding stage persona, earned him the nickname “Prince of Darkness.” However, Davis proved to be a dazzlingly protean artist, moving into fiery modal jazz in the ’60s and electrified funk and fusion in the ’70s, drenching his trumpet in wah-wah pedal effects along the way. More than any other figure in jazz, Davis helped establish the direction of the genre and whose influences can be heard in the genre-bending approach of performers across the musical spectrum, ranging from funk and pop to rock, electronica, hip-hop, and more.

Prince

No other musician can compare to Prince. Perhaps a peer could match him for an individual skill, whether it was as a singer or guitarist, but no individual could match him as a package: a vocalist and instrumentalist of distinctive vision, an inventive songwriter and innovative producer, and a pop conceptualist with an expansive, idiosyncratic vision. At his popular and artistic height in the ’80s, this vision seemed to crystallize on Purple Rain, but he could not contain his imagination to the confines of his own records, either with or without his backing band the Revolution. He masterminded albums by the Time and Sheila E and gave away hit songs to the Bangles and Sheena Easton, shaping the sound of popular music in the process. There wasn’t an area of pop music that didn’t bear his influence: it could be heard in freaky funk and R&B slow jams, in thick electro-techno and neo-psychedelic rock, and right at the top of the pop charts.

Pink Floyd:

Some bands turn into shorthand for a certain sound or style, and Pink Floyd belongs among that elite group. The very name connotes something specific: an elastic, echoing, mind-bending sound that evokes the chasms of space. Pink Floyd grounded that limitless sound with exacting explorations of mundane matters of ego, mind, memory, and heart, touching upon madness, alienation, narcissism, and society on their concept albums of the ’70s. The band’s sonic signature was always evident: a wide, expansive sound that was instantly recognizable as their own, yet was adopted by all manner of bands, from guitar-worshiping metalheads to freaky, hippie, ambient electronic duos. Unlike almost any of their peers, Pink Floyd played to both sides of the aisle: they were rooted in the blues but their heart belonged to the future, a dichotomy that made them a quintessentially modern 20th century band.

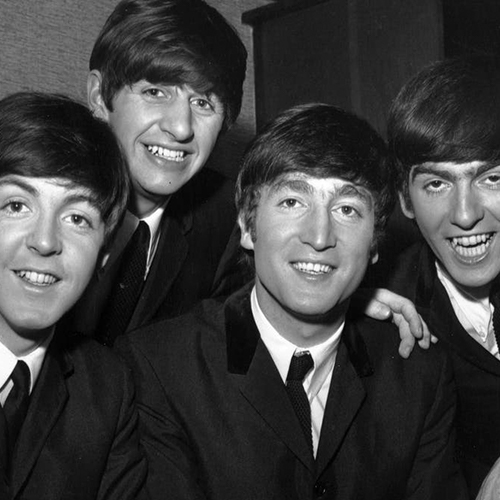

The Beatles:

It’s hard to recognize today just how innovative The Beatles were in their time. To start with the obvious, they were the greatest and most influential act of the rock era, and they introduced more innovations into popular music than any other group of their time. Moreover, they were among the few artists of any discipline that were simultaneously the best at what they did and the most popular at what they did. They synthesized all that was good about early rock & roll and changed it into something original and even more exciting. They established the prototype for the self-contained rock group that wrote and performed its own material. As composers, their craft and melodic inventiveness were second to none; they were key to the evolution of rock from its blues/R&B-based forms into a style that was far more eclectic, but equally visceral. Their supremacy as rock icons remains unchallenged to this day, decades after their breakup in 1970.

Day One Listens is written by Allan Grant, Chief Operating Officer of Day One Leadership. Through stories of how music has influenced key parts of his life, he will regularly profile artists and albums that have created lasting impact; helped him to grow over time; and practice self-respect every day. The author graciously acknowledges the contributions of various online reviewers, specifically at allmusic.com, who aided in providing insights and remarks related to the specific artists/albums mentioned.